Nothing has changed

Technology has been the key to exposing how far we still have to go

Like you, I was horrified by the videos from Memphis. Normally (and how horrible is it that I can use that word in this context?), I avoid watching the video evidence of this sort of state-sponsored violence. I know it’s there. I know it’s real. I don’t need it seared into my brain.

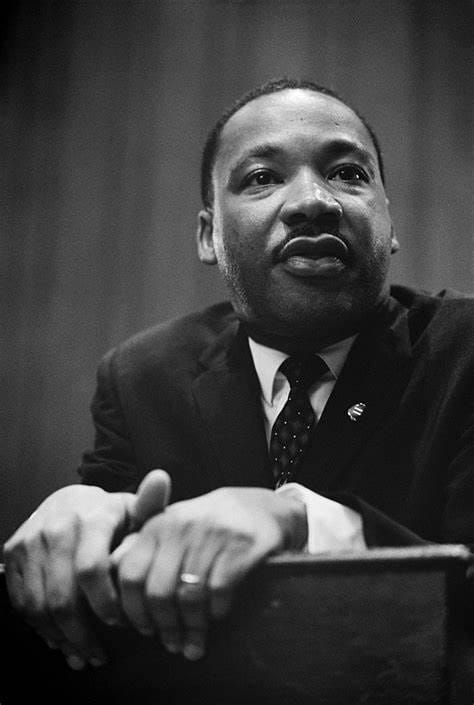

But this time I didn’t change the channel. And what I saw brought horrible flashbacks to the 1960s. Specifically, 1968, when my teenage brain staggered to process the back-to-back assassinations of Bobby Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

I am grateful that those cameras are here today to document the atrocities in a way that was not possible in 1968.

It did not help my soul last night to remember that Dr. King was gunned down in Memphis, within spitting distance of this, the latest atrocity in America’s Deep South. And it reminded me of one of the longest, most powerful sentences ever written.

But when you have seen vicious mobs lynch your mothers and fathers at will and drown your sisters and brothers at whim; when you have seen hate filled policemen curse, kick and even kill your black brothers and sisters; when you see the vast majority of your twenty million Negro brothers smothering in an airtight cage of poverty in the midst of an affluent society; when you suddenly find your tongue twisted and your speech stammering as you seek to explain to your six year old daughter why she can’t go to the public amusement park that has just been advertised on television, and see tears welling up in her eyes when she is told that Funtown is closed to colored children, and see ominous clouds of inferiority beginning to form in her little mental sky, and see her beginning to distort her personality by developing an unconscious bitterness toward white people; when you have to concoct an answer for a five year old son who is asking: “Daddy, why do white people treat colored people so mean?”; when you take a cross county drive and find it necessary to sleep night after night in the uncomfortable corners of your automobile because no motel will accept you; when you are humiliated day in and day out by nagging signs reading “white” and “colored”; when your first name becomes “nigger,” your middle name becomes “boy” (however old you are) and your last name becomes “John,” and your wife and mother are never given the respected title “Mrs.”; when you are harried by day and haunted by night by the fact that you are a Negro, living constantly at tiptoe stance, never quite knowing what to expect next, and are plagued with inner fears and outer resentments; when you are forever fighting a degenerating sense of “nobodiness”—then you will understand why we find it difficult to wait. There comes a time when the cup of endurance runs over, and men are no longer willing to be plunged into the abyss of despair. I hope, sirs, you can understand our legitimate and unavoidable impatience.

That, of course, is from the Letter from Birmingham Jail, by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I read that letter in its entirety every year to remind myself of how far we’ve come and how very very very far we still have to go.

I know many white people are struggling to come to terms with the realization that the country they grew up in is irredeemably racist, even above the Mason-Dixon Line. Rather than expound on that, I will point you to the wise words of Sherrilyn Ifill, who read one post by a white man describing one such struggle and responded with grace and clarity.

Sherrilyn Ifill: A Response to Conor Friedersdorf

That is the moment that we are in. The outrage is perhaps even more intense, albeit less inclined to express itself in mass protest. It is combined now with the growing sense that the current system is simply not sustainable. The failure of the police response in Uvalde, and the lack of support shown by the most rabid pro-police political factions towards the Capitol Police officers assaulted on January 6th, 2021 has been a huge blow to law enforcement that will have repercussions for years to come, as will the revelations of infiltration by openly white supremacists groups into law enforcement agencies. Unraveling mythologies is a long process. But once it starts, the end is inevitable.

And that leads back to the premise of Friedersdorf’s piece. Where should we assign blame for continued police violence? On the failure of the movements created by racial minorities to resist police brutality? On crime within our own communities, as some suggest? Yes, violent crime is real, and felt most profoundly in minority communities. We want solutions more than anyone, but refuse to believe that we must surrender our dignity and the lives of our sons and brothers to police violence, in exchange for protection from violent crime.

I suggest that what Friedersdorf sees as failure, is instead his own inability to recognize the power and resilience of white supremacy, and its hold on the institution of American law enforcement. Those of us in this work have long explained the systematic and cultural hard-wiring of racism in policing, while so many leaders in the white community have insisted that it is only “bad apples.” We explained that so deeply-imbedded is the culture of white supremacy in policing that even Black police officers can participate in brutality against Black victims, because they too are responding to the messages of white supremacy in their profession that promotes and rewards officers who know whose lives matter and whose don’t.

Read, as they say, the whole thing.

I close by reminding everyone that Dr. King was in Memphis to organize civic action on behalf of sanitation workers who had gone on strike to protest horrifying working conditions. If you have never read the history, maybe you should.

In the later 1960s, the targets of King's activism were less often the legal and political obstacles to the exercise of civil rights by blacks, and more often the underlying poverty, unemployment, lack of education, and blocked avenues of economic opportunity confronting black Americans. Despite increasing militancy in the movement for black power, King steadfastly adhered to the principles of nonviolence that had been the foundation of his career. Those principles were put to a severe test in his support of a strike by sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee. This was King's final campaign before his death.

During a heavy rainstorm in Memphis on February 1, 1968, two black sanitation workers had been crushed to death when the compactor mechanism of the trash truck was accidentally triggered. On the same day in a separate incident also related to the inclement weather, 22 black sewer workers had been sent home without pay while their white supervisors were retained for the day with pay. About two weeks later, on February 12, more than 1,100 of a possible 1,300 black sanitation workers began a strike for job safety, better wages and benefits, and union recognition. Mayor Henry Loeb, unsympathetic to most of the workers' demands, was especially opposed to the union. Black and white civic groups in Memphis tried to resolve the conflict, but the mayor held fast to his position.

Very little has changed in the big picture. Working people, especially people of color, are still exploited today. The baseline of poverty might have changed, but the reality of profound inequality has gotten worse, not better.

The one very large thing that has changed is technology. The Memphis police were not allowed to work under cover of darkness. Those cameras exposed the sordid truth. And they are not going away.