The security software industry wants you to be afraid of the "dark web"

An industry whose very existence is predicated on selling fear has found a new bogeyman.

These days, credit card companies are falling over one another to offer perks that differentiate them from the competition. And as part of the benefits that come with my Chase Sapphire Preferred card [1], I get occasional reports about my credit score and activity on (pause for dramatic effect) the “dark web.”

Here’s an email Chase sent me today. The tone can be paraphrased as “Nothing to be alarmed about, sir, but perhaps you want to climb into your fallout shelter before you click this link.”

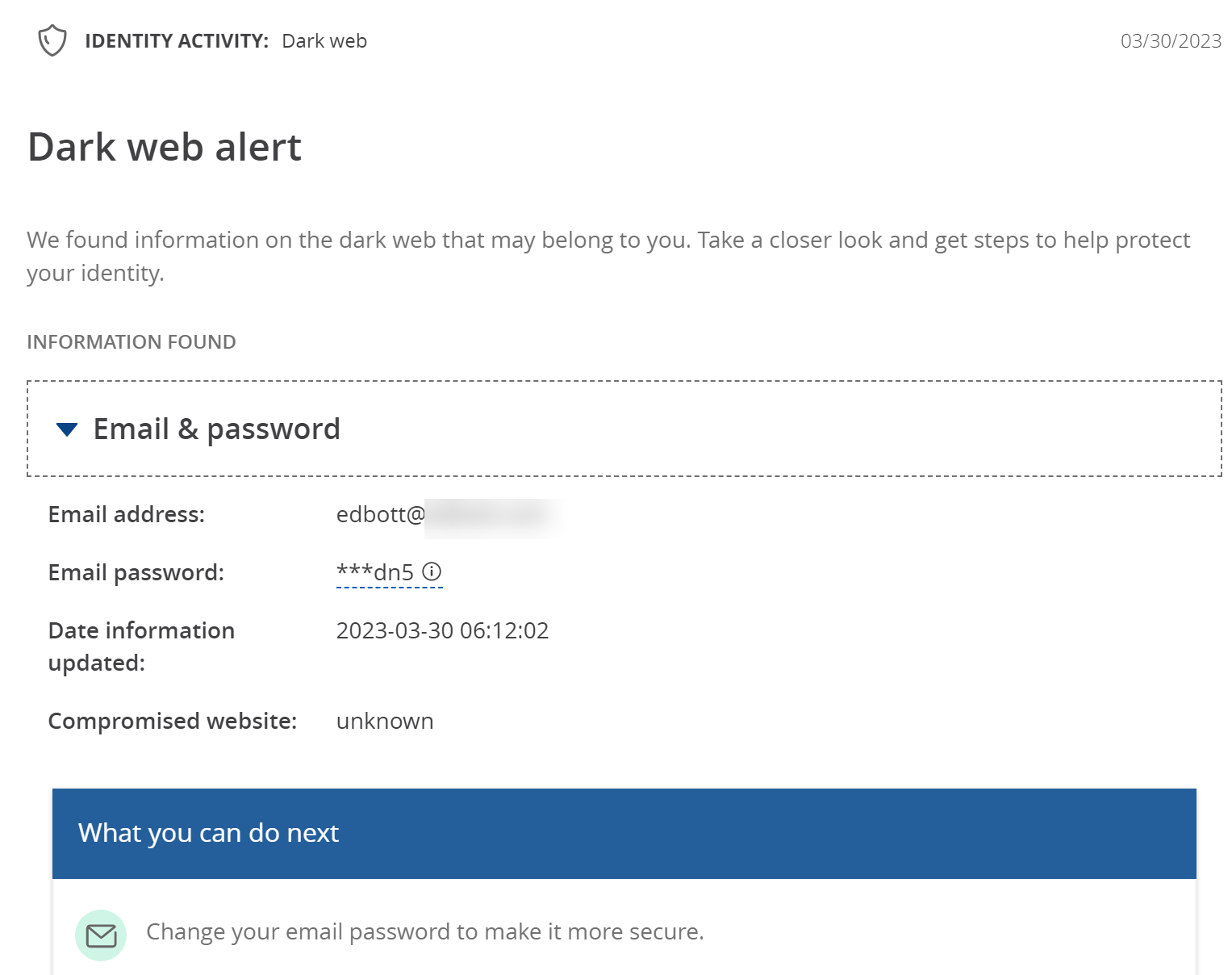

Clicking that link sent me to the Chase website, where (after signing in) I was presented with a “Dark web alert” webpage that informed me my email and password from a “compromised website” had been found somewhere online. The report was … not exactly filled with technical details. See for yourself:

So, what’s going on here?

I must admit, I was baffled by this one. That snippet of a password doesn’t resemble anything associated with the email account in question. Nor does it help that this “dark web report” doesn’t provide even a clue as to where this sketchy information is from or what website or online service it might be related to. I looked through several lists of known data breaches from the past year or two and couldn’t find anything that matched up with this.

Eventually, I hit on a strategy. I exported my 1Password file (usernames and passwords only) [2] to an Excel worksheet to see if I could find any password I had ever used that included the segment shown in this email message. Surprisingly, it worked. I had indeed used that email address and a password containing those three letters to sign in to my LinkedIn account.

But I changed that password in 2012. No, that is not a typo; I really did that more than 10 years ago! That happened right after LinkedIn reported that their accounts database had been hacked. (I found that detail because my password manager helpfully added a note documenting every password change.)

Those LinkedIn credentials have been bouncing around the Internet for roughly a decade, and I guess the file got dumped to a new site recently, leading to this alert.

It’s all horribly misleading, though. That sketchy alert implies that my email account has been compromised and recommends that I change my email password to make it more secure. Why should I do that? This set of credentials wasn’t associated with that email account; the email address was simply serving as a username for a completely unrelated service.

In my considered opinion, sending notification of a compromised set of credentials from a data breach that happened more than a decade ago isn’t exactly an “alert.” I’m sure the Chase marketing people who partnered with whatever company is providing this data believe they’re providing a valuable service, but all they’re really doing is adding noise to an already cacophonous security soundscape and encouraging me to waste a lot of time changing passwords that don’t need to be tampered with.

But here’s the thing: If I didn’t know enough to figure out that this alert was very old news and not an indication of a real problem, I might be impressed that the credit card company was looking out for my online security.

I wrote about this phenomenon nearly two decades ago, in a 2005 post titled “The security software industry wants you to be afraid.” (Here’s an archived version of that post, in case you feel like reading about online security in the age of Windows XP.) A fellow tech journalist had written a glowing thank-you note to the maker of his Windows PC for installing commercial antivirus software on his computer, which they did to collect a commission from the software maker. That software in turn had popped up a warning message that made him believe the software had detected a nasty piece of malware and saved his PC from infection. But it was a false positive and there was no threat there at all.

Joe feels good because the software told him it had protected him, even though the likelihood that this was an actual attack is microscopic. The lesson that Joe is unwittingly sending to the vendors in question is, “Give me more false positives, because the more times you tell me you’ve protected me from something, the more I’ll feel like I’ve gotten my money’s worth from your software.”

Meanwhile, back in 2023, when I went looking for security vendors selling dark web monitoring services, I found the usual suspects (Norton and McAfee at the head of the list) along with a surprising number of companies serving enterprise customers. CrowdStrike, for example, says “Who Needs Dark Web Monitoring Services? The short answer: Everybody.” Which is a pretty bold growth hacking strategy, I guess.

There might be a case for enterprise IT folks to pay someone to monitor underground sites for early signs of data breaches or intrusions. But do consumers get any value from this info? I’m skeptical.

CrowdStrike, though, says I need to get busy:

What does it mean if your information is on the dark web? For consumers, the revelation that their information is available on the dark web usually means they should change all their passwords, keep an eye on their credit reports and consider replacing their credit cards.

Uh, change all my passwords and replace all my credit cards? No. Thanks, but no.

I regularly hear from readers who had a close brush with some sort of malicious software or phishing attack. In most cases, they tell me they responded by spending too much money on a security software suite that promises comprehensive protection from every imaginable threat. They were afraid, which made them perfect targets for companies that prey on their fear.

Be afraid. After all these years, that pitch still works.

[1] That’s a referral link to the Chase card. If you sign up for the card you get a 60,000 point bonus, worth anywhere from $600 to $750 . I recommend it because you can get 3% cash back for dining and most streaming services, and it has no foreign transaction fees.

[2] If you try a similar strategy, make sure you save the exported password file to a local directory and then permanently delete it after your check is complete.